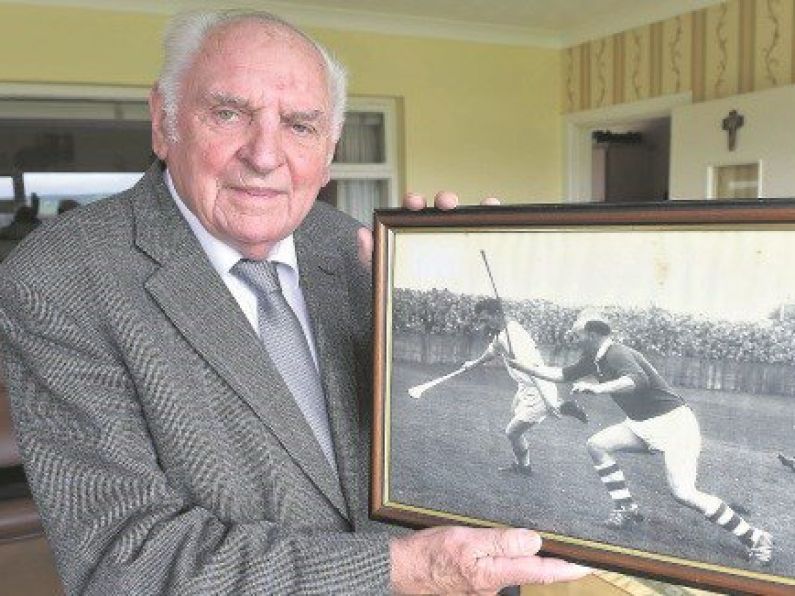

A survivor of Waterford’s last All-Ireland win in 1959, Austin Flynn manned the Déise square at a time when his chief responsibility was to ‘protect the goalkeeper from being killed’. His policing was thorough, even when assigned the cases of greats such as Nickey Rackard, Liam Devaney, and Christy Ring, who became a great friend as much as foe.

In his second coming as a Waterford hurler, Austin Flynn, who tonight receives a Hall of Fame gong at the Munster Council’s annual awards ceremony in the Fota Island Resort Hotel, won an All-Ireland medal, a National League medal, three Munster medals, and a Railway Cup medal.

It was quite the era, the Déise’s greatest, and he was an integral part of it at full-back.

But the opening chapter of the Flynn story is a tale worth telling too, if only to illustrate the trough into which the game in the county had so suddenly and inexplicably sunk between the towering peaks of 1948 and 1959.

On a summer’s night in 1952, a young Flynn was coming home from the pictures in Dungarvan when he found Michael Fives, the Abbeyside GAA chairman, and Seaneen O’Brien, the club captain, waiting for him at the Poor Man’s Seat.

He’d been called up for the Munster quarter-final against Clare the following day, they told him.

Far from being elated, Flynn was surprised, even upset. This was big news all right, but for him it was a bridge too far, too soon. His informants weren’t having any of it.

“You can’t leave the village down tomorrow,” warned O’Brien. “You’ll have to turn up.”

Hoping he wouldn’t be called upon, Flynn travelled into Waterford the next day and came on as a substitute.

The match ended in a draw. He kept his place for the replay in Thurles, where he was picked to mark the great Clare forward Matt Nugent. Clare won but were run over by Tipperary in the semi-final.

And that was it for Flynn for the next five years.

Waterford weren’t going anywhere in particular and he had no desire to accompany them. Looking back on it, what strikes him most forcefully now is the fact the county had done the All-Ireland senior and minor double (“an amazing achievement”) only four years earlier, in 1948.

“Things had slipped so much in a short space of time. We were so disorganised.”

They were so disorganised and there was no indication they’d be organised anytime soon.

Here ended the First Coming of Austin Flynn.

Eearly 1957, an evening in Fraher Field. The Second Coming of Austin Flynn.

This time it’s serious. This time it’s for keeps. Because Waterford, at long last, are serious.

Pat Fanning, the new chairman of the county board and a future GAA president, is addressing the members of the panel.

Fanning is a wonderful orator and tonight he isn’t sparing the rhetoric.

“As God is my judge,” he announces, “I believe there’s the winning of an All-Ireland for Waterford in this team. It will take a great effort. “You will have to give a great commitment. You will have to give until it hurts and then give more. Everything possible will be done by the county board.

“But lads, it’s a matter of pride in the Waterford jersey. Cork and Tipperary and Kilkenny have their tradition. But we have our tradition too.

"It’s easy to come back when you’re winning. Picking yourself up and coming back for more — that’s Waterford’s tradition.”

To Flynn the words were nothing less than an epiphany. He’d been happy with life as it was, playing hurling and football for Abbeyside and messing about with boats.

He’d just finished building a 16-footer with his brother, based on the model of a stormy petrel in a book of boat plans someone had given him and, in the absence of marine plywood, fashioned out of larch from the priory in Mount Melleray.

“I was fulfilled. I had no great ambition to play for Waterford again. That all changed that night in Fraher Field.”

Pat Fanning knew whereof he spoke. Within a few months Waterford were Munster champions with a team built around a golden generation that had burst out of Mount Sion, supplemented by a barnstorming centre-forward from Ballyduff in Tom Cheasty.

They were beaten by a point by Kilkenny in a classic All-Ireland final but gained their revenge two years later in a replay. League success and a third provincial medal followed in 1963.

Memories? Flynn has plenty.

Liam Devaney, who died recently, scratching his head in bafflement at one of thenine goals Waterford hit to beat Tipperary, the reigning All-Ireland champions, in the 1959 Munster semi-final. (“I was as surprised as he was.”)

Seamus Power soloing in and hitting the shot that Jim the Link Walsh, the Kilkenny full-back, deflected past Ollie Walsh for Waterford’s late equaliser in the All-Ireland final.

Victory in the replay four weeks later and the rattle of the lorry as it made its way across Rice Bridge the following night with the new champions aboard.

If Fanning was the group’s inspiration, a speaker so gifted that “you were ready to break down the door for Waterford or die in the attempt”, John Keane, the centre-back on the 1948 team, was their trainer and unofficial psychologist.

From The Enda McEvoy Interview Irish Examiner