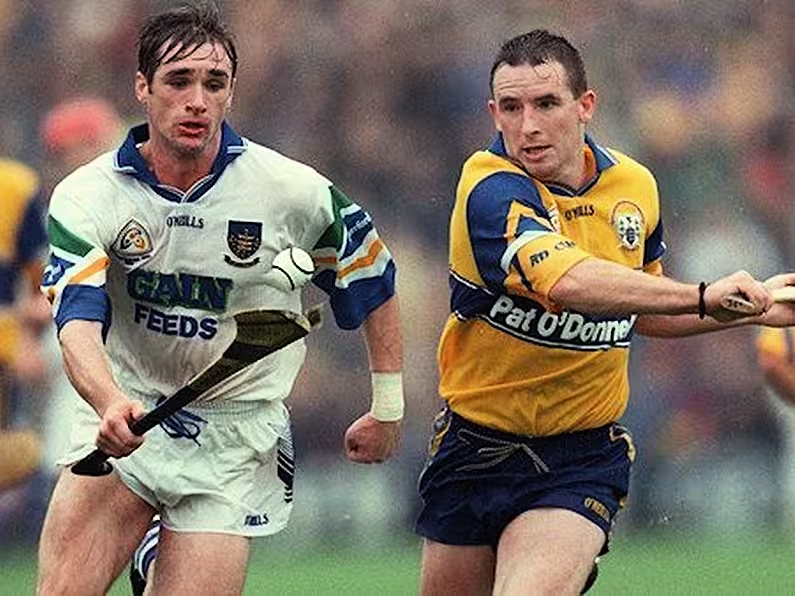

Who dares to speak of ’98? Tony Browne, actually, but 21 years after his infamous scrape with Colin Lynch, the Waterford legend’s regard for his opposing number on the Clare side is immense.

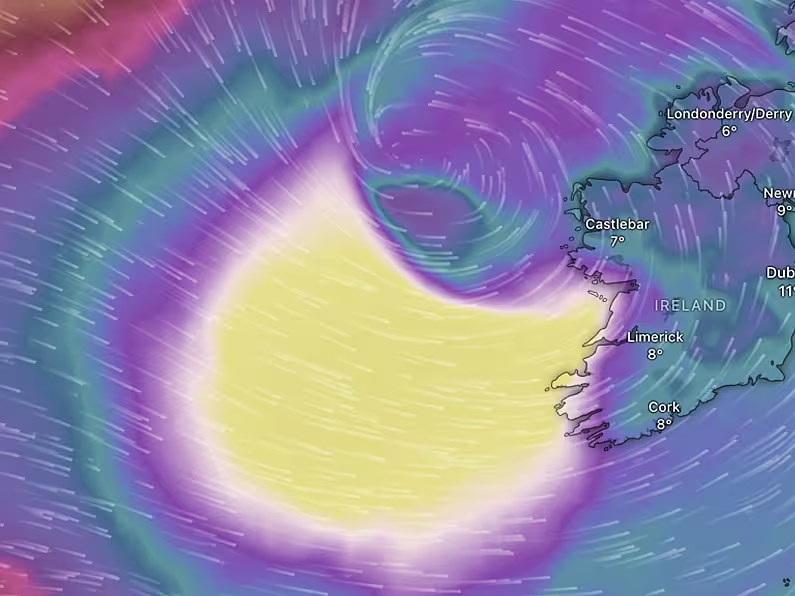

After missing out on a game and place to call home last summer, Waterford is humming now that we’re just days out from Clare coming to town.

There’s been a fierce scramble for tickets, like you’d normally only get for an All-Ireland or for a Munster final when it was still something rare and novel to the county.

Everyone not only wants to be in Walsh Park, everyone wants to make a difference. To help turn it into something of a fortress and a cauldron, much like Clare themselves have done with Cusack Park.

I was in Ennis when the two teams also met for Waterford’s opening game of last year’s championship.

I’d no sooner taken my seat near the back of the covered stand when I could hear a young fella behind me grumble to the man next to him: Is that Tony Browne?

Next thing I could feel two knees wedged right into my fifth lumbar vertebrae where they remained for most of the afternoon. Every time I pushed back, the knees would be straight back in! As I laughed to my wife beside me, it was like ’98 all over again! Clare lads getting stuck into me before a ball was ever thrown in, doing their bit to try to rattle the other crowd!

The other day on the radio Derek McGrath made the point that now in Waterford we have the opportunity to return such hospitality and transform Walsh Park into the hurling equivalent of Galatasaray’s old Ali Sami Yen Stadium, where visitors were infamously welcomed to hell.

But to be honest, I’d stop short of that and I’m sure Derek wasn’t being literal either — at least until the ball is thrown in. As far as I’m concerned, anyone from Clare is more than welcome to Waterford.

In fact I’d hope and urge as many Clare supporters as possible try to come down on the Saturday night. Have a few pints and give some business to a few establishments that have supported Waterford GAA well down the years.

As Kieran Delahunty famously quipped to Anthony Daly back in ’92 when we beat them on my championship debut in a near-empty Semple Stadium, they’re into their traditional music in Clare, so to make them feel at home, I’m sure a few hostelries in town will gladly provide a bit of trad over the weekend.

And some blaas to sample and savour on Sunday morning.

And of course we can chat and have the crack with them about hurling. Even ’98.

It’s 21 years ago now. Passions and relations between the counties have cooled down. It’s safe to talk about the war, a war without bullets as Loughnane once described it.

There’s a generation now who have either no memory or even awareness of the events of that year, but for any of us who were around and lived it at the time, we’ll never forget.

It was a year and campaign like no other. For Loughnane and his team. For me. Even for hurling itself.

I was 24 heading into that season and to be as blunt about it as Gerald McCarthy was with me when we met on the eve of it, it was make or break time, buddy.

I was five years on from making my debut the same day Delahunty and Daly traded digs at one another, and other than blocking a ball Sparrow whipped on just after I came on in the last couple of minutes, I’d made next to no impact at senior championship level. I hadn’t won another game. Every subsequent year our championship had been over after just one game. Tipp, Limerick, it was the same story. We’d lose.

We’d even infamously lose to Kerry in ’93 but I wasn’t around for it. I’d dropped myself off the panel. Even though I was still short of my 20th birthday, I could just tell how off the whole set-up and culture was, though a word like that wouldn’t have been en vogue back then the way it is now.

I remember one evening one of our physical therapists had to stand in goals. Looking back I often feel sorry for brilliant players like Delahunty and Damien Byrne.

I remember in one of my first league games, playing in the half-back-line and being absolutely creased by Brian McMahon, an All-Star at the time, and Byrne coming over and picking me off the ground the same way you’d pick up a kitten by the scruff of the neck.

But as a county we weren’t looking after the likes of him and the teams he soldiered on with.

The year after the Kerry disaster, I’d return, and with the U21s we’d win Munster, beating Clare in the final, just as we had on our way to winning the All-Ireland in that grade in ’92.

But to be honest I was soon part of the problem and malaise.

You’d train on a Tuesday and a Thursday and have your pints as well as your match at the weekend, sometimes in that order.

Gym was just something that sounded like the name of Brian Greene’s dad. Looking back on it now, if Gerald McCarthy hadn’t come in when he did, we might have ended up going where Offaly are now.

Gerald changed everything, grabbing everyone by the neck. County board. Players. Me. I remember him sitting me down before 1998 and telling me that I could be anything I wanted to be but I needed to knuckle down and bulk up.

I had to be the change I wanted to see in the world.

Truth be told, though, I was already thinking like that after seeing what had gone down in ’97.

Clare had won another All-Ireland, not least because of the fresh impetus provided by a whirlwind of physicality and energy around midfield by the name of Colin Lynch.

I’d played against Colin and most of his Clare teammates in those Munster U21 finals of ’92 and ’94. But instead of us pushing on, they were the ones driven by those nights in Thurles and Fermoy.

Now seeing them being the ones handed the silverware was forcing me to up it. I wanted what they had.

I only envied them, though. And admired them. Never disliked them. If anything, I could relate to them more than any other group of players in the country.

One autumn I was away with a few of them for a shinty international in Inverness, Mike Mac as the team manager and me as the token Waterford guy, someone from the weaker counties you could say.

And of all the counties that were represented on that trip, the crowd that I clicked and gelled with the best were the Clare lads. Especially Colin.

His background would have been similar enough to my own.

There were seven of us in my family and all of us were sent out to work once we were finished school. As far as I can remember or knew, Colin didn’t go to college either. He was just a salt-of-the-earth guy, no airs, no graces.

Hurling as well as life hadn’t always been kind to him — he missed out on Clare’s breakthrough in ’95. And so on that trip to Inverness, it was often Colin’s company that I fell into. Talking. Drinking. Laughing. And after being in his orbit, I wanted to have a year in ’98 like the one he’d had in ’97. He was the standard, the benchmark, an inspiration.

We trained like dogs for ‘98. Whatever Mike Mac put the Clare boys through in Crusheen or wherever else, Gerald did that and more with us below in Waterford.

I remember us doing flat-out one-mile runs and seeing fellas wobbling on the verge of fainting as I passed them by.

I particularly recall one morning down by the Baldy Man in Tramore, plodding up its dunes and running that 4k stretch of beach.

Your feet would sink so far into the sand, it’d go right up to your knees. Halfway up running one particularly murderously steep incline for the 10th time that day, I puked.

And as I was wiping the vomit off my face, I said to myself: ‘I ain’t doin’ this for nawthin’. This has to be for something. All-Ireland. All-Star. Munster. I had to have something to show for this.

And that was my state of mind all that year. Even — especially — in those manic few seconds either side of the throw-in of the Munster final replay. Nothing was stopping me from winning something. Nothing was going to throw me off stride.

The whole of the Clare team, not just Colin — in fact the whole of the west of Ireland — could have tried to break their hurleys off me that day.

My mind and goal wasn’t wavering. I never even felt a thing. Not least because, looking back on the video, Colin’s pulling was so wild, I think Ollie Baker and Peter Queally got more slaps of his hurley than I did.

It was only a few years ago I saw that film 42 about Jackie Robinson, the first black ball player to play Major League Baseball. There’s a scene just before he’s signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers where the team owner, played by Harrison Ford, outlines to Robinson the importance of him retaining his poise.

If he were to retaliate and lash out any time a fan or opponent had a pop at him, he was finished and it could set back race relations another 10 years.

Initially Robinson’s baffled. “You want a player that doesn’t have the guts to fight back?!” Ford’s character, Branch Rickey, shakes his head. “No. No. I want a player who’s got the guts NOT to fight back.”

That was exactly my outlook in ’98. The easy thing would have been to just strike back and lash out. That was the prevailing culture of the time.

Looking back there was an awful lot of macho, argy-bargy crap in hurling and football at the time: slipping a bit of timber into the ribs of your marker, or in the football, throwing him a nasty dig.

But for me it took a stronger person to rise above all that. Lash out and strike back and you could get sent off. Cost our people the chance of winning a match or a Munster title we’d gone so long without.

And cost myself an All-Star as well, since in those days a straight sending-off ruled you out of having any chance of making it onto the red carpet up in the Burlington.

I was expecting a reaction like that from Clare and Colin. And so I was prepared for it. I’d been man of the match in Waterford’s two earlier championship games, including the drawn game the previous week, and Clare were hardly going to want or let me make that three games on the trot. But in my mind they weren’t going to deter me either.

After Willie Barrett’s attention was drawn to a scuffle between Brian Lohan and Micheál White, Colin had another go at me and we tussled for a bit.

I was going to stand my ground but again, I wasn’t going to lash out and end up missing the rest of the game and the whole of the All-Ireland series. There was too much riding on all this for me to be sitting on the line.

Clare would end up winning that Munster final. And no doubt Loughnane would attribute it to the war-like pitch he had his team at.

But I’m not so sure. I don’t think they needed to go down that road. In all honesty I think they were simply a better team than us in ’98. Better balanced. They were better than everyone that year.

But that’s not to say we couldn’t still have won the All-Ireland.

And with how everything caught up on Clare, we should have won it. That wasn’t a great Kilkenny team that beat us by a point in the semi-final. And we’d have seriously fancied ourselves against Offaly.

But the Munster final caught up on us as well.

Although we’d hammer Galway the week after that Munster final replay, Gerald would get suspended for the semi-final after some of his brushes with the officials during the Clare games. And not having him on the line against Kilkenny meant a few crucial switches weren’t made.

Looking back on it, Clare and ourselves bate each other to that All-Ireland. Colin got suspended for three months, even though he should never have been the way he was and for as long as he was, and Gerald would finish the year in the stand as well.

The authorities wanted to censure us in some way, while they’d been waiting for a good deal longer to put manners on Loughnane and Clare. What should have been an all-Munster All-Ireland instead ended up being an all-Leinster affair.

Over the following few years we’d be slow to forgive the other for that but a whole lot quicker to remind them. Clare really delighted in stopping us in 2002 up in Croke Park after we’d finally won in Munster.

Then in 2004 when we met them in Thurles in the first round in Munster, Davy Fitz tried it on again. At one stage early on he shouted in my direction, “We’ll f****n’ do ye over like we did in ’98!” I fired back, “Sure, Davy, I was hurler of the year in ’98, thanks to ye!” Like everyone else with Clare that day, poor Davy didn’t know what to say or do.

I was only half-joking too.

They did make me hurler of the year in ’98. If they’d kept their poise, if they’d shown a bit more of the emotional control which I did that day in Thurles, then a Clare man most likely would have been hurler of the year and collected the Liam MacCarthy as well.

In going overboard to win a particular battle, they lost the war.

Although my ankle and body was black and blue after that Munster final replay, just from going up against the likes of Colin and Baker in general play, nothing was going to stop me from winning things that year.

After a week of the best physio and recovery and sea water you could find, I suited up the following Sunday to play my first ever game in Croke Park.

We’d thump Galway in that All-Ireland quarter-final and I’d end up man of the match again. And when I reflect on it, that game was huge in the development of Waterford hurling.

We hadn’t played or won a senior championship game there in 35 years. Had we lost, much of the good vibes about ’98 — reaching a league and Munster final — would have dissipated. We wouldn’t have had the same platform to build upon.

That win put us sitting at the top table and we’ve been there pretty much ever since, though never sitting on the top seat of that table.

Thankfully I’d play plenty of more games up in Croke Park, though I’d have loved a few more in September.

And I’d be fortunate to have had a good few more championship games going up against Colin. My respect for him never dimmed after ‘98. We’ve bumped into one another a few times since he’s retired.

Never a bad word between us, always only a civil one.

But if I’d lashed back at him, got myself suspended, would I have ever played in Croke Park? Would Waterford have won the following day out against Galway? Could it have put us back 10 years?

Branch Rickey was no fool.