By Aine Kenny

Coping with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) can be challenging at the best of times, but it is even more difficult in the middle of a global health pandemic.

Many of the behaviours stereotypically associated with OCD, such as repeated hand washing, wearing gloves, and continually cleaning surfaces are now being encouraged.

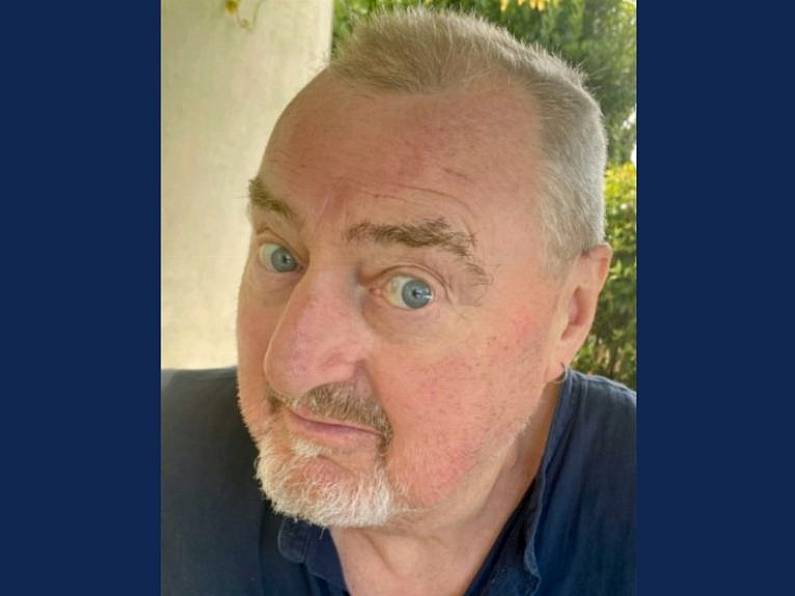

Dr Pádraic Gibson, who specialises in treating the condition in the OCD Clinic in Dublin, said he has seen a spike in people presenting with the condition in the last month or so.

However, OCD varies greatly, and different anxieties bring different challenges.

“It’s a very complex disorder and there’s a lot of aspects to it,” said Dr Gibson.

He said people with OCD often have mental obsessions and work can be a distraction for them. However, because of the pandemic more people are unemployed or working from home.

“It’s hard for them to get the obsessions out of their head,” said Dr Gibson.

“Now that they are home more often with loved ones and family members, the [other members of the household] can see the strange or bizarre behaviours they could have been concealing.”

Dr Gibson said three things people with OCD often do are seek reassurance, avoid things, or try to control things with rituals.

“A lot of people are getting more reassurance or continually monitoring things, for example if they have health anxiety. They might be obsessed with getting Covid-19. They are continually getting push notifications about Covid-19, reading articles about it, seeing it on the TV, and hearing it on the radio.”

Avoidance is another common trait associated with OCD, and if the workplace was causing severe stress for someone with OCD, more time at home can be a relief, said Dr Gibson.

However, if this is maintained for too long, it becomes difficult to break out of the pattern of avoidance.

Seeking control through ritual can be another trait associated with OCD.

“If you have structured your day in a certain way where you can manage in a ritualised way, and that day is interrupted in some way, it can become very distressing for people.”

Dr Gibson said for people who do have OCD, it is important for them to combat their own behaviour.

“Watch what you are avoiding. For example, if you have a fear of harming someone, or doing something wrong, by avoiding it you will worsen the problem,” he said.

“When you avoid a situation you communicate a very dangerous double message to yourself, ‘I’m safe because I am not around the kids or certain items’, but you confirm your obsession or fear by avoiding it. So avoid avoidance as much as possible.”

For those who use rituals, Dr Gibson said that introducing some disorder into these rituals can help.

“Learn how to delay or postpone the ritual, or change the sequence of how you are doing them.”

He also said it is important for family members to not ‘collaborate’ with the problem, which can be extremely difficult if someone is distressed.

“You can listen to the problem, but try not to collaborate with it,” he said.

“Parents need to try not to wash down surfaces for the person, which can be very hard to do. It can really worsen the problem and they become held hostage and trapped in the cycle as well.”

He also said the best thing is to seek specialised treatment as early as possible.

“Many people cover it up because they are ashamed of their behaviours, but there’s nothing we haven’t heard before.”

Case study: ‘I was scared of the colour blue, the number 4’

Rebecca Ryan first noticed symptoms of OCD when she was just four.

“It wasn’t until the age of 13 that it actually exploded into a diagnosable issue,” said the Co Clare student, who now goes to college in Limerick.

Rebecca noticed she was atypical in that she was scared of certain things, such as the colour blue and the number four, because they all had “different meanings”.

“I was scared that they were going to cause death,” she said.

“I was scared of any word that was to do with medicine or the medical system. I was scared of knots in wood, of certain numbers on the clock.”

Rebecca also experienced compulsions, such as feeling that she had to make certain movements with her body.

“It was very disruptive and I couldn’t work very well in school. Sometimes I couldn’t leave the house,” she said.

Rebecca undertook cognitive behavioural therapy when she was 13, and this, combined with medication, helped her greatly.

A common misconception is that people have to have an obsession with cleanliness to have OCD, which is not the case, she said.

“Anything can be an obsessive thought.

“The motivation to perform a behaviour to get rid of a certain thought that makes you uncomfortable is a symptom of OCD.

“Definitely go to your doctor and definitely set yourself up for therapy. It may not work at the start but you will get better with it. Taking medication is not a failure. It just means you need a little bit of extra help.’

Rebecca said friends and family need to be patient.

“This [pandemic] is a heightened experience for everybody, not just for people with OCD, although the experience will be magnified for them,” she said.

Rebecca encourages people to apply the tools they have learned in therapy, such as cognitive behavioural therapy and exposure response prevention techniques.

“But don’t be too hard on yourself if you can’t do too much, because this is a stressful and unprecedented time,” she added.

“To people with OCD — you are not alone, you are not less intelligent, you are very much the same as everyone else. You just have an issue that needs to be taken care of, similar to someone with a broken bone. It’s just the stigma that sets you apart. You’re going to be absolutely fine.”

Case study: 'Don't make yourself a prisoner in your own home'

Clare Doyle is a nurse from Wicklow. She’s had OCD since she was 15.

Now 49, she gained a degree in psychology in 2017, which she said gave her another understanding of the condition.

“I have different types of OCD. I have done exposure therapy, it worked for some things and didn’t work for others. I have never gone down the medication route.”

Clare has also managed to develop a strategy whereby she can refocus her thinking, and this works for her.

She does have contamination OCD, and in the past, this manifested itself in fears surrounding the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1990s.

Clare said having contamination OCD is challenging during this Covid-19 pandemic also.

“I have my ways of dealing with it and it isn’t a problem, so I don’t need to do any exposure therapy. I feel sorry for people who do have OCD and are supposed to be doing exposure therapy because I am not sure how they are managing.

“The two things that increase anxiety levels are loss of control and uncertainty,” she said.

“With the Covid-19 pandemic, there is a lot of uncertainty surrounding the virus, where it came from, who could potentially be infected, when it will recede.”

Clare thinks many people who didn’t have OCD may experience symptoms now.

If you tell the brain something is really important, like it is really important to wash my hands properly, to clean the shopping trolley, the brain will develop a habit of telling you it is really important to do these things.

Clare encourages people with OCD to seek professional help as well as talk to family and friends.

She also said it was important for people not to isolate themselves.

“If you have an OCD way of thinking, there could be no end to [reading up about the virus online], and you could end up not going out at all... go out, get your shopping, follow guidelines but... don’t make yourself a prisoner in your own home.”