When I was 40, a friend of mine died. He was a fellow member of the Worker’s Party. He developed cancer which subsequently metastasised throughout his body.

I think of him in his hospital bed for what would be the final time. His face was ashen, his stomach was distended from the disease which now consumed him. I think of a proud and dignified man, a campaigner, a husband, a father, laid to waste and left in unbearable pain by a brutal and terminal illness. My friend died some weeks later.

During my first term as a TD, my office was contacted by a man seeking help for his wife. He said she was suffering from a degenerative condition, multiple sclerosis (MS), and was seeking legislative support so that she may, at a time of her choosing, be assisted to die. The man’s name was Tom Curran and his wife was Marie Fleming.

Marie was diagnosed with MS in her 30s. As the years passed, her condition worsened to the point where Tom gave up his job and became her full-time caregiver. In her later years, a promise between herself and her husband - that when the time came he would assist her to die - kept her going. It motivated her battle all the way to the Supreme Court to have the State recognise her right to a dignified death.

Marie's case was rejected by the Supreme Court in April 2013. However, the presiding judge did note there was nothing to stop the Oireachtas from legislating to allow for assisted suicide once it was satisfied that appropriate safeguards could be put in place.

Marie Fleming passed away in December of that same year. Her story, which touched so many people throughout Ireland, along with the support of her husband Tom led to my involvement in developing what would become the Dying With Dignity Bill.

The draft bill was completed in 2015 and introduced as a Private Member's Bill but, due to the collapse of the government the following year and my subsequent appointment as a minister of state, I was not able to move it forward for debate. I tried many times to liaise with other politicians but, despite productive conversations, none would take ownership of the work that had been done.

I believe this legislation could still bring about significant and welcome change for those suffering from terminal illnesses. At its core, it proposes to amend the Suicide Act of 1993 so that a medical practitioner who provides assistance in accordance with the Act, by prescribing and administering a substance to assist with ending a qualifying person’s life, would not be guilty of a criminal offence.

Those qualifications include:

- A qualifying person must be terminally ill with an incurable and progressive illness that cannot be reversed by treatment and who is likely to die as a result.

- They must be 18 years or over and be a resident in the Republic of Ireland for not less than one year.

- They also must have a clear and settled intention of ending their own life and make a declaration to that effect in the presence of a witness who cannot be a beneficiary of their estate.

- This declaration must be signed off by two medical practitioners.

- A minimum of 14 days must have elapsed between the signing of the declaration and the administration of the substance.

Of course, many will disagree with the bill, but look at examples of other countries where medically assisted suicide is legal, such as Canada, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Sweden, or some states in the US.

A 2007 study found rates of assisted dying in Oregon, the first US state to legislate for assisted suicide, and in the Netherlands showed no evidence of heightened risk for the elderly, women, people with low educational status, the poor, the physically disabled or chronically ill, minors, people with psychiatric illness, or racial or ethnic minorities.

Additionally, a study of hospice workers in Oregon reported that symptoms of pain, depression, anxiety and fear of the dying process were more pronounced among those who did not request aid-in-dying medication.

Irish society has undergone radical social change over the past five years, the kind which was once thought impossible. This was made clear by the outcomes of both the Marriage Equality referendum and the Repeal of the 8th amendment, both of which passed by roughly a two-thirds majority.

A 2019 Amárach/Claire Byrne Live poll for TheJournal.ie found that around 55% of people believe that assisted suicide should be legalised in Ireland.

Assisted dying is different to same-sex marriage and termination of pregnancy, though. It is the most personal decision that can be made.

People forget that you should be entitled to a dignified death. It is unbearable to think that somebody is going to die and that their suffering should be prolonged.

The time has come to debate the Dying with Dignity Bill in the Dáil. We must consider those living with terminal conditions, the likes of Marie Flemming or my Worker’s Party comrade, and finally legislate for dignity in death.

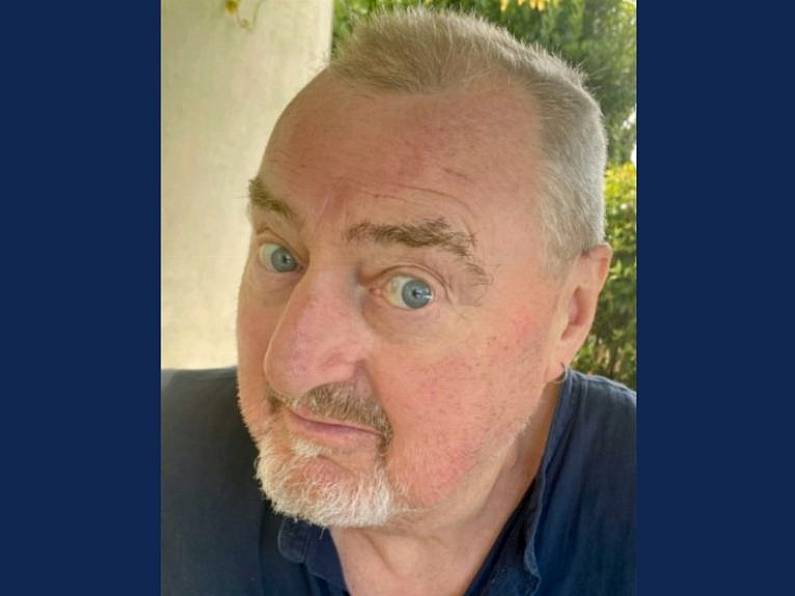

John Halligan is a former minister of State. He served as a TD for Waterford from 2011 to 2020.